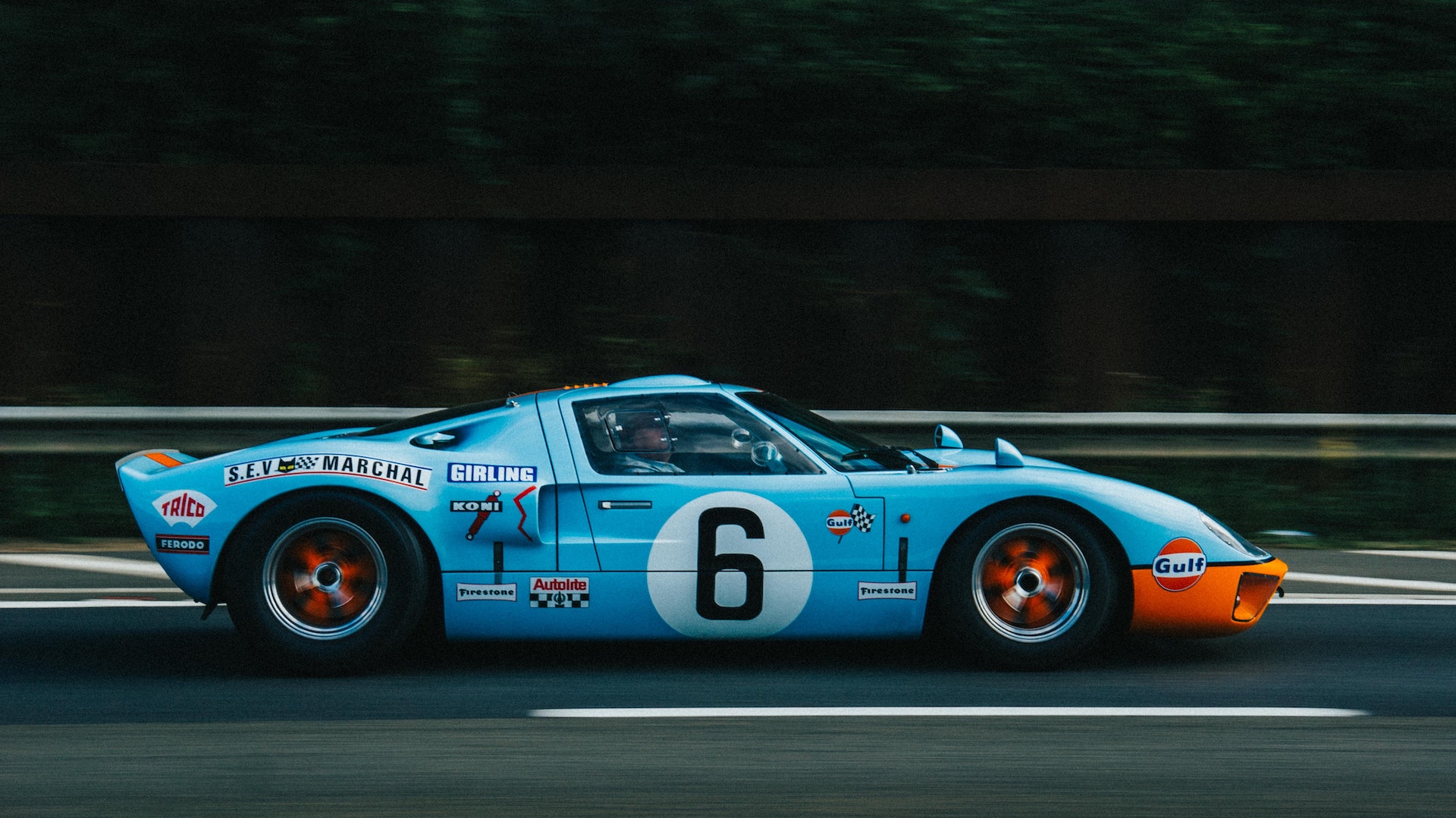

The Ford GT40, a Brilliant Masterpiece of Automotive Performance and Art

Part 1 – Epic Rivalry Spawns Genius Racing Machine

Prestige, speed, engineering, endurance, ego, supremacy, power, influence, victory, and money—lots and lots of money. The saga of the legendary Ford GT40 super racer, the first American car to win the prestigious 24 Hours of Le Mans, has all that and more.

Colossal Power Players—Hank the Deuce vs. Il Commendatore

The beginning of this story could be called buying what you don’t have, or trying to. That’s what Ford Motor Company attempted in the early 1960s when the consumer tastes of newly affluent Baby Boomers shifted from practical transportation to cars that were sporty, fast, distinctive, and fun. Unlike General Motors and Chrysler, Ford had nothing to offer, contributing to a serious slide in sales.

Henry Ford II, who was perhaps the most famous and powerful CEO in America in the 1960s, decided the quickest way to gain sports car products was acquisition; he proposed buying Ferrari to fill the gap. Led by founder and former race car driver Enzo Ferrari, the Maranello, Italy-based company’s primary focus was putting fast cars on race tracks, which it had done repeatedly since production of the first Ferrari-badged car in 1947. The company won its first race in May of that very year, took its first checkered flag at Le Mans in 1949, topped the Formula One World Championship Grand Prix in 1951, and throughout the 1950s and early 1960s was the marque to beat. Meanwhile, the company sold just enough street-legal cars to fund its racing ventures.

Realizing that his company needed additional resources to remain successful, Enzo, known as Il Commendatore for his outsize temper and tyrannical control, was amenable to talking with the equally strong-willed Deuce. After months of negotiation, by spring of 1963 an agreement seemed to be in place—until Ferrari understood that a clause in the contract gave Ford control of the budget and all decisions affecting the Ferrari racing team. Enzo promptly nixed the deal, reportedly adding choice words of insult about Henry II compared to his grandfather Henry Ford and denigrating the quality of Ford cars and trucks. The newswire release issued on May 22 was more polite: “Ford Motor Company and Ferrari wish to indicate, with reference to recent reports of their negotiations toward a possible collaboration, that such negotiations have been suspended by mutual agreement.”

Outraged, outwitted, outfoxed, and embarrassed, the Deuce promptly pledged to build a race car capable of humiliating Ferrari at Enzo’s most prized competitive venue, the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

The GT Program Book Roars to Life

Long the pinnacle of speed and endurance, the storied 24 Hours of Le Mans has been run annually in June since 1923. The famed 13.6-kilometer (8.5-mile) Circuit de la Sarthe road course is located near Le Mans, in northwest France. The route includes 9 kilometers on public roads and 4.5 kilometers of asphalt track. The race lasts precisely 24 hours; the car that covers the greatest distance in that time wins. Three drivers must alternate in each car; no one individual can drive more than a total of 14 hours. Especially crucial and tricky is the 6-kilometer Mulsanne Straight, where speeds routinely reach more than 200 miles per hour. The stretch is interrupted by two chicanes requiring extreme braking that abruptly slows cars to 40 mph. The reputation of Le Mans as a punishing test of mechanical expertise, human perseverance, styling practicality, engineering insight, and even luck is well deserved.

The fact that Ferrari had won at Le Mans in 1949, 1954, 1958, 1960, 1961, and 1962 (the streak continued unbroken through 1965) goaded Henry II into action. The Deuce wanted a Ferrari Killer, and he wanted it now. This despite the fact that Ford had little history with high-performance endurance racing or machines capable of competing at, let alone winning, such events.

But Hank’s word was law, and by mid-June 1963 the High Performance and Special Models Operation Unit was formed; its mission according to documents from Ford Archives: “To design and build a racing GT car that will have the potential to compete successfully in major road races such as Sebring and Le Mans.” The confidential GT Program Book circulated shortly thereafter and contained initial design concepts for a GT40 race car. Among the revolutionary ideas proposed by engineer Roy Lunn was making the overall height of the car just 40 inches. Hence the name GT 40—GT for Gran Turismo and 40 to mirror the specs for the car.

Joining Lunn on the Ford Advanced Vehicles team were several luminaries whose names live on in automotive lore: British engineer Eric Broadley, developer of the flashy, mid-engine Lola Mk6, one of the era’s most advanced race cars; 1959 Le Mans winner Carroll Shelby (then driving for Aston Martin) as consultant for the project; and Brit John Wyer, who had managed Shelby’s victorious 1959 Le Mans team. The group set up shop near London’s Heathrow Airport and went to work. They had a mere 10 months to get ready for the 1964 Le Mans race.

Learning from Disappointment in 1964 and 1965

By April 1964 the first GT40 was completed. But potentially deadly issues were quickly apparent as New Zealand driver Bruce McLaren (another legend) guided the car on the test track and during time trials at Le Mans. Speed was impressive from the outset, but overall, the GT40 was unstable, unreliable, and difficult to control at high speeds. Moreover, the brakes threatened to melt and fail when applied at the end of the high-speed Mulsanne Straight. The team quickly made modifications, including adding a spoiler, just as the racing season began.

Speed was never a problem, but endurance was. Despite setting a lap record (during its first Le Mans, no less!) all three Ford cars entered in 1964 were out with gear box, suspension, and other failures after 12 hours, only half of the required 24. Following DNFs at other venues, by the end of the year the GT40 effort was clearly in trouble. Ford management, with Henry’s agreement, moved the entire program to the U.S., and put car designer/entrepreneur/automotive icon Carroll Shelby fully in charge, with strict instructions to accomplish the GT40 goal of winning Le Mans. Roy Lunn continued as chief engineer.

Shelby quickly engaged developmental driver Ken Miles, an Englishman known for flamboyance and daring behind the wheel. Miles and the team made numerous modifications to suspension, aerodynamics, airflow ducting, materials, and wheels; performance immediately improved. During the first outing of the year, Fords, for the first time, completed an endurance race, placing first and third. But time trials in April at Le Mans were not encouraging; Ferraris dominated while Ford experimented constantly with different engines, gearboxes, brakes, suspensions, and other components, desperately searching for something that worked.

Fortunately, the engineering team in Dearborn had been busy getting yet another new GT40 version, called the GT40X, ready for testing. After figuring out how to squeeze Ford’s mighty 7-liter 427-cubic-inch engine into GT40’s limited mid-engine real estate, the team cheered when the car hit a blistering 210 mph on the test track straightaway. Lead driver Miles immediately declared, “This is the car I want to drive at Le Mans this year!”

Which he did, setting a new record of 3:33 during practice laps, almost five seconds faster than the Ferraris. Unfortunately, the actual race was a disaster. Mistakes in assembly during the build in Dearborn led to gearbox failure in the two 427 cars entered in the race, plus 289 engines in cars supplementing the fleet proved to be unstable. Despite the poor showing, Ford PR chief Leo Beebe delivered a rousing pep talk to the discouraged GT40 team. “Next year we’re going to come back here and win, and we might as well start now.”

IN THIS SPACE NEXT TIME, THE TALE CONTINUES. COME BACK TO SEE HOW GT40 WENT FROM NON-EXISTANT TO LE MANS WINNER IN AN ASTONISHING THREE YEARS!