Ford Woody Wagons – Fun, Cheerful, and Stunning to Behold

Imagine … stripping and varnishing the bodywork on your car – annually!

Yet owners (or their chauffeurs, assistants, or hired woodworkers) were willing to perform this annual ritual to keep their woody wagons glowing and pristine. Or so it was by the latter 1930s. By then woody wagons had become the purview of wealthy families, captains of industry and commerce, political kingpins, and film stars, as they luxuriated in this exclusive accessory to their good fortune. The annual revarnishing ritual became part of the woody mystique.

But the woody didn’t start that way.

From Utilitarian Origins …

First designed as hackneys for hire, woodies were practical carriers used for commercial transport. Eventually, the term station wagon emerged to designate such vehicles since their purpose became hauling well-heeled travelers from stations (most people traveled by train) to fancy resorts, lavish estates, exclusive country clubs, and private hunting lodges.

Primitive station wagons go back to the earliest days of the automotive industry and like most early cars were made mostly of wood. These early utilities were custom-built by third-party coachmakers, who crafted wooden bodies and placed them atop a truck or large car chassis, adding bench seats and room for storage. A wooden roof mostly kept the rain off, but side curtains were rare and windows unknown. In 1923, the short-lived Star Car was the first company to offer a factory-built station wagon, with the wagon body delivered to the Star assembly plant and fitted to the chassis there.

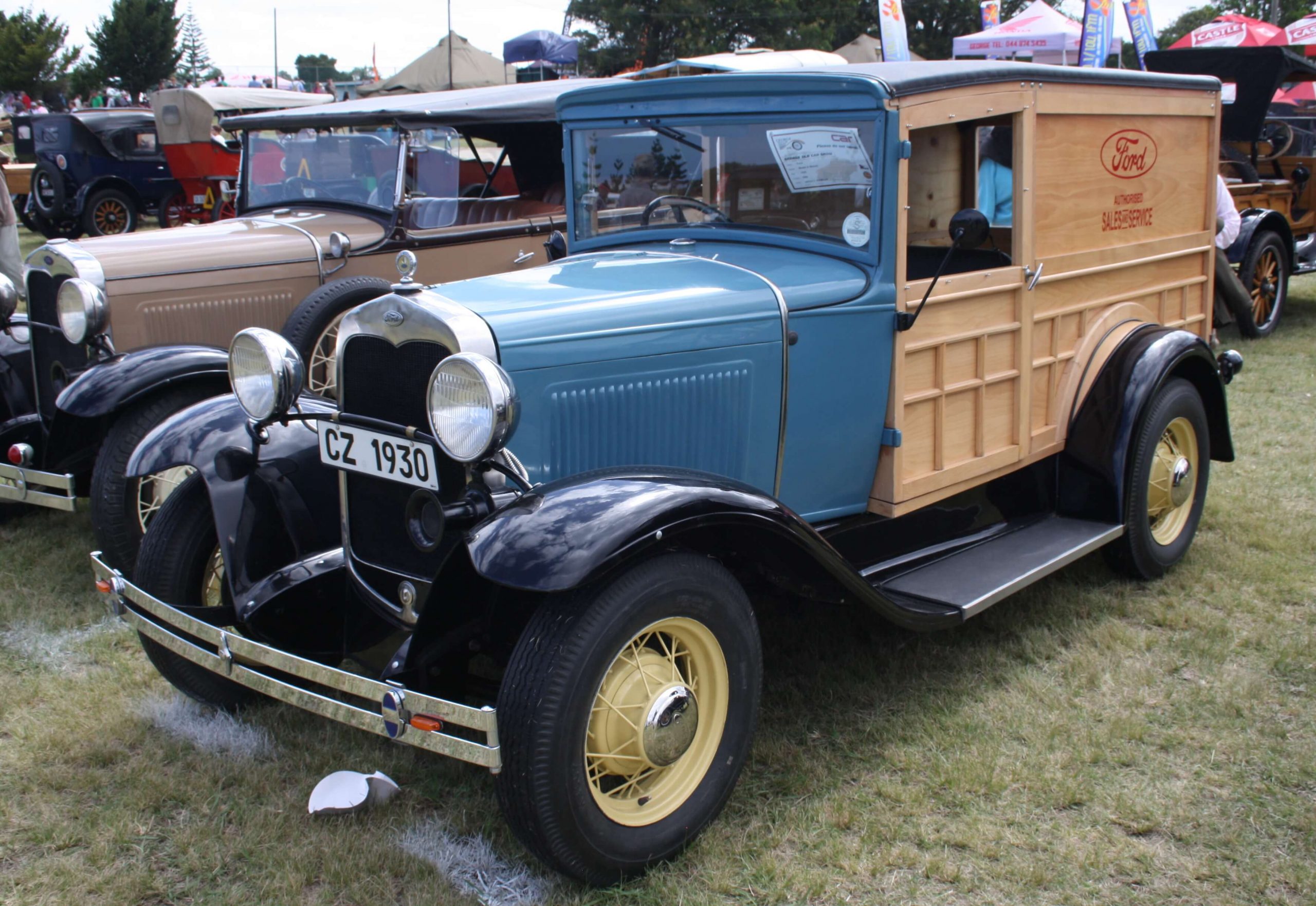

Ford recognized the potential of such vehicles and in 1929 came out with a mass-produced woody (or woodie – both spellings are used), the first of the Big Three manufacturers to do so. Although it was advertised as a commercial truck rather than a passenger car, interest grew. Ford made 5,200 that first year, selling for $695 each.

Such vehicles were still largely hand-built and featured mostly wooden bodies throughout. Gradually, shaped steel came to form the engine cowl, grill, fenders, and other elements from the windshield back, although that material was more expensive during the early woody years and knowledge of stamped metals was still in its infancy.

Also, Henry Ford believed in wood as an essential component of automobiles. After all, his first cars were motorized carriages, and carriages had, for centuries, been made of wood. In 1920, he purchased more than 400,000 acres of forest reserves in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and constructed a plant nearby. For a number of years, production of wood parts was centered in the area, with Ford handling all operations internally, from growing trees to cutting timber, to running a sawmill, to forming body parts, including those for the woody station wagon.

That 1929 Model A wagon body was made mostly of hard maple, with birch or mahogany inserts and sweetgum for paneling. The cabin was completely handmade of wood, including the headliner, doors, dashboard, and tailgate. There were four doors, with the rear doors attached at the C pillar, opening toward the back. Through 1934, only the windshield was glass, with all other window openings covered in canvas curtains with small plastic openings.

… to High-End Luxury

Although every major manufacturer eventually built woody wagons, it was Ford’s 1935 and 1936 models that really distinguished the company as America’s luxury wagon leader. In 1935, crank-up glass windows were featured in the front doors, with an optional rear glass window added a year later. The 1937 swing-out rear window was an industry first. Equipping woodies in 1936 with the Ford flathead V8 engine gave them 85 horsepower, which was an appealing complement to the new radiator grill and front-end design. Mechanical improvements across the entire Ford lineup improved reliability and provided a better driving experience. Interiors went upscale as well, with plush leather seating and commodious accommodations for multiple passengers.

Throughout the decade, steel replaced wood in many applications. Yet Ford woodies retained real hardwood for major sections of the vehicle exterior – the warmth and elegance of wood had a sophisticated, cultivated appeal. Station wagons with wooden bodies came to exemplify the epitome of premiere craftsmanship, refined grandeur, polished decorum, and elegant taste. They also denoted wealth and status, since considerable upkeep and near constant maintenance were required.

Woody No More

Though born of necessity, woodies were never a particularly sound business proposition, especially as the art of steel stamping became more widespread. Manufacture of woodies was extremely time-consuming since much of the work was done by hand and required the expertise of well-trained craftsmen. As many as 150 separate pieces of wood were involved in the production of a single vehicle, with the weight of the wood adding 200-300 pounds to each one. Glued and screwed seams came loose frequently, producing squeaks, rattles, and groans. Bodywork demanded as much attention as the finest wooden boats. But there was something about Ford woodies that made them magical, even though, according to some sources, the company consistently lost money despite the woody’s allure.

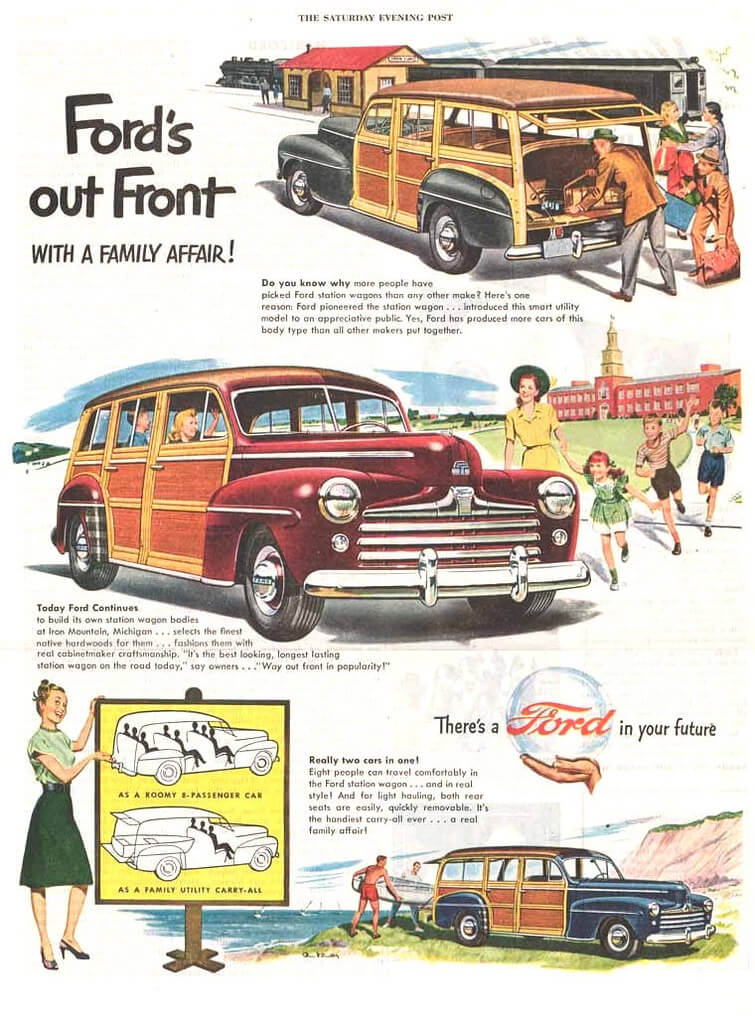

When civilian auto production resumed in July 1945 after the three-year hiatus mandated by World War II, woodies badged for both Ford and Mercury were central to Ford’s strategy. Even though wagons built from 1946 to 1948 were largely unchanged from 1942 models, a major redesign was planned for 1949.

Unfortunately, a change in corporate direction, the need to economize quickly (Ford was losing $10 million a month), and the introduction of all-steel wagons by competitors doomed the woody, which was the most expensive vehicle in the entire Ford/Mercury catalog to produce and sell. The last true Ford woody was built in 1948. By 1949, Ford was shipping steel wagon bodies to the Upper Peninsula factory, where the only wood was in tacked-on outer panels. Rather than the solid pieces of maple used for earlier body framing, vehicle underpinnings were now constructed with an electrobonding process, and door frames were formed by a 75-ton press applying pressure to a package of resin-coated plies as they fed into a frame pillar blank. Although 1951 Ford and Mercury wagons set an all-time high in the number of woodies produced, they were the last wagons with real wood bodywork of any kind. The handcrafted magic of woodies was gone.

Woody Restored

The introduction by Ford of all-steel wagons in 1952 relegated woodies to history – except they weren’t totally forgotten. For a time in the 1960s, they became cult vehicles immortalized in song and sought out by surfers for their immense carrying capacity. Surviving woodies became prized collectibles, proudly exhibited at Concours and classic car shows, although original models are fairly rare. That’s in part because wood rot claimed many woodies – the vehicle just didn’t hold up over time. Also, when the final woodies were built, dealers were supplied with kits of replacement wood so owners could restore deteriorated panels themselves. But most owners weren’t interested, and dealers eventually threw out the wood cluttering their premises, making truly original replacement woody stock exceedingly difficult to find.

Today, at auction, authenticated original woodies can draw well into six figures, although plenty of less costly examples are out there as well. Restorers and customizers snatch up woodies as quickly as they find them, and gladly invest time and money in painstakingly bringing them back to life. From collectors, restorers, and even passersby, a true woody – vibrant, gorgeous, and stunning – is guaranteed to elicit a reverent, admiring wow!