The Culmination of a Race Car’s Life

and Its Builders as Well

NOTE: This story was written in 2006 as the result of a press conference for the APA. One of the volunteers who helped restore the Goldenrod also pitched the story to me.

Bill Summers waited his turn for the podium under the skylights at the famous Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, MI. Others told the basic story of the long, sleek race car under the silk cover while Bill looked on beaming with pride. Dignitaries and dozens of members of the Detroit Automotive Press Association were assembled to hear this fascinating story.

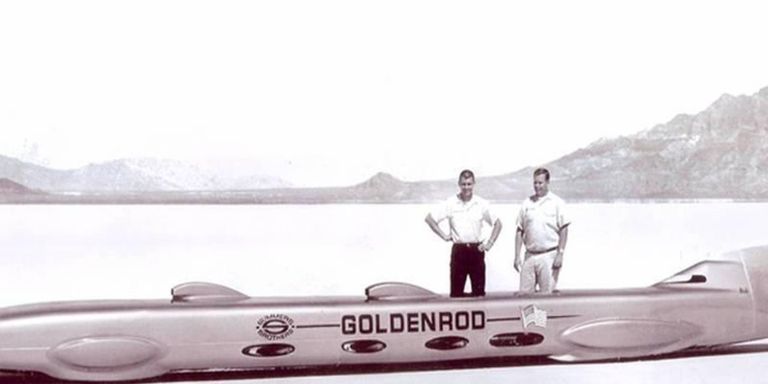

Bob Casey, curator of transportation at The Henry Ford, told how Bill and his late brother Bob, two young fellows totally untrained in engineering, entirely self-taught race car builders, designed and built this 32-foot-long Bonneville racer with 4 naturally aspirated Chrysler Hemi engines that took the land speed record from British racers who held the record since the 1920s. Their speed was over 400-miles-per-hour. That was 1965. The Summers Brothers’ record held until 1991.

With a little assistance, 70-year-old Bill Summers mounted the podium. It took him a few minutes to gain his composure a he was overcome by the emotion and significance of the event. He told me later that, “this is the culmination of the car’s life . . . and the culmination of mine.” Summers told a number of fascinating stories about how the Goldenrod came to be and how it became the record holder for all those years.

He talked about his good friend Ray Brock buying brother Bob a suit so he would look presentable when hustling sponsors. Summers described quitting his job as a truck driver the day George Hurst handed him a check for $5,000, breaking the ice that encouraged Firestone, Mobile Oil, Chrysler and the Champion Spark Plug Company to throw their money and expertise into the pot, making it possible for the brothers to build and campaign their car.

He told about building the car in a shed, formerly a vegetable stand, barely bigger than the car at 15X40-feet. Summers told about acquiescing to the insistence of the Chrysler engineers that the air scoops be enlarged to get more air to the engines, when in fact the car ran faster with the smaller, more aerodynamic intakes they had designed.

And, he told how the Goldenrod got its name from the wonderful ’57 Chevy gold paint and from its hot rod heritage.

Chrysler loaned the brothers four 426-cubic-inch Hemi V8 engines. The Summers brothers mounted them end-to-end, two facing forward, two facing the rear. Two five-speed truck transmissions with first (creeper) gear removed were mounted one at each end of the car. Everything was connected with custom-built drive shafts and linkages making those engines and transmissions pull together in as simple a fashion as possible. Tube chassis, body panels, and everything else were hand built by the brothers who had built dozens of race cars over the years, just for the sheer fun of racing – just for the sheer joy of going fast.

Bob was the driver, the thrill-seeker, the guy with the need for adrenalin. Bill was the practical, natural-born mechanic and instinctive engineer. As youngsters they worked well together because they both loved racing, in the classic Southern California hot rod sense.

The fateful day came on November 12, 1965. The car was ready but the weather at the Bonneville Salt Flats had not been good over previous weeks. It was too wet and windy most of the time. As the weather cleared the course was committed to others and it looked like the Summers Brothers would have to wait until 1966 for an attempt. By then the sponsor dollars might not hold out. But, good fortune was with them. Art Arfons, friend and fellow racer, had just set a new record for jet-powered cars and had “salt time” left. He called the Summers Brothers and told them if they could get there PDQ they could have the time.

The vegetable stand in Ontario, California must have been chaotic as they packed everything up and burst out of there for Bonneville. Warm up and practice went well. Finally, the support truck pushed the Goldenrod out to the starting area and onto the course. She fired up and off she went. The first 6-mile run was 417-mph and some change. She was still accelerating at over 400-mph as Bob reached down with both hands between his legs to shift into fourth. Bob, not one for excessive verbalizing, once described the cars handling as similar to being guided by a string – straight and true. Good thing, since it takes two hands to shift that hefty linkage.

To be an official time it takes two runs and the team had an hour between them to fuel, adjust and prepare for the second. With five minutes to spare Goldenrod was off again for the return run. Conditions were still good, everything worked just right and the rest is history – average speed through two runs: 409.277 mph. Beating those arrogant Brits by a comfortable margin (more than 6-mph), proving that good American ingenuity could get the job done simpler, lighter and for a fraction of the cost of the last car to set the record.

As brother Bob the race car driver came in after his return run, having set the world land speed record for wheel-driven cars, the timer asked if he wanted to take another shot at it, perhaps go a little faster. He had a glint in his eye and was thinking about it when brother Bill, the team manager, called it a done deal. It was too expensive, and too dangerous to tempt fate like that when they didn’t need to.

Things changed significantly after that. Bill went on a number of world tours with the Goldenrod – visited Europe five times, he’s proud to say. His reception in Brittan was not as congenial as elsewhere since. After all, it was a long-standing British dominance of the sport that he and his brother defeated. Bill and the car were one for many years. Chrysler had taken back their loaned engines – a good thing, Bill shared, since the car was much lighter to truck around without all that weight.

Bill and Bob went into business making and selling specialty race car parts, particularly axles and gear drives. But their life views were quite different, and they found it more and more difficult to work together.

Bob ‘Butch’ Summers died in 1992.

The Henry Ford, which includes both Greenfield Village and the Henry Ford Museum, got wind of the Goldenrod’s availability and purchased it in 2002. Part of the cost of restoration was covered by a federal grant from Save America’s Treasurers. The only other motor vehicle to be supported by this grant is the Rosa Parks Bus, also in The Henry Ford collections.

Mike Cook of California oversaw the restoration. A second-generation hot rodder himself, Cook is past president of the Southern California Timing Association, official land speed record sanctioning body. The car was in dismal shape, he reported, with severe salt damage to the aluminum bulkheads and many other parts. The restoration philosophy was to save as much of the original car as possible even if that meant a less than perfect result. This is, after all, a magnificent artifact, not a show car.

Being purchased and restored by one of the most prestigious museums in the country – perhaps the world – is akin to being inducted into a hall of fame. Bill Summers was humbled and honored by the attention afforded him, his brother, and particularly to the legacy of the legendary race car called Goldenrod.

Visit www.thehenryford.org